All photographs, text, and graphics in this website are © David Lee Myers

Site updated

23 February 2021

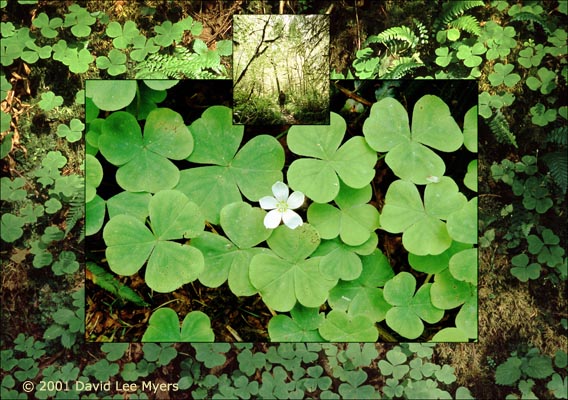

Alexandra's Walk. My wife is off on a spring hike in the Queets River Valley of Olympic National Park. These three photos were made as she started. 2001.

Loving the Wild Woods

I walk into a rainforest grove, one fortunate to have matured for a thousand years without a catastrophe of wind or fire, of slide or saw. The ceiling, the arboreal canopy, is lifted high into another world by columnar trunks stout beyond my measure. From a clear sky come shafts of hot sunlight, etching textures with inky black edges and painting crisp colors. I look toward the sun, into rays coming through green broad leaves and conifer needles, making stained glass windows in the forest canopy. This vast space is at once intimate and untouchable; no wonder it’s so often felt as a cathedral. Close at hand the ornamental details are myriad and minute beyond recounting: Cup fungi—chalices for dew drops, spore capsules held aloft on thread-thin stalks, a heron’s feather and, in my gentle fingers, the burnt orange belly of a wriggling rough-skinned newt.

Two worlds of light are interlaced—one in the sun, one in the shade. It’s hard to see or photograph them both together, yet the shapely edges between the zones best convey the drama of life in this biological tapestry. When the sky fills with clouds, soft light wraps around edges, gently modeling the shapes of trunks, shrubs, and stone. I especially enjoy moments when the two kinds of light come into balance. Rain-wet leaves may add another dimension of reflected color and sparkle.

I have walked and photographed in many of the Northwest’s old forests—both ancient forests which have never been logged, and others which have been cut, partially or long ago. Each one has its particular mix of leaves and space, of old and young trees of different species, and shrubs. In some groves the filigree of shrub leaves is made by elderberries, in others by rhododendrons. I find sitka spruce on the wettest foggy slopes and bottoms, douglas-fir on wind-ripped ridges. Why are there western redcedars in this grove but not in another? Everything I figure out in the woods or learn from books or people sharpens my observations and opens up new questions. Each plant, bird, or sound, every process in the forest life that I learn engages my attention to a new aspect of the woods and helps me see. A quiet mind and attention to the sounds and fragrances of the woods, the feel of the ground underfoot and the lay of the land, the breeze and the mist or rain, and the light, all help me become aware.

I visualize a cycle: A tree grows for many hundreds of years. It falls down, softens and decays for hundreds of years more. Its remains nurture another generation—seeds sprout on it, seedling roots growing first into the old log, then reaching around it into solid ground. Long after the fallen tree has melted into earth, it is remembered in the arch of the roots which remain, or in a straight row of trees whose beginnings it nurtured. To turn this great biotic wheel just once takes nearly a thousand years.

A tree’s memory is not mental, fast, and fugitive like mine, but lies in the structure of its rings and trunk, its roots and branches, chronicling hundreds of years of opportunities accepted, difficulties overcome, and threats survived. Growth rings were fat in the wet years, spare in the dry ones. Swelling buttresses grew to brace against the storm winds. A trunk curved to compensate for the slumping of its earthen footing. Branches grew into unused light, avoiding the shadows of neighbors. Lightning pruned and scarred a tree, making more room for another to reach the sky’s light. In such ways forests remember longer than do people.

My great love of forests is rooted in my photographing the ancient forest remnants of southwest Washington. There I learned that when I tried to photograph just a single magnificent tree, my results disappointed me. Instead I discovered photographing forest communities, the assemblages of many trees and other plants whose lives intertwine in space, giving each other both shelter and competition. Gradually I learned more about these interconnections, which became a satisfying aspect of my photography.

I’ve also learned the joys of nearby, more ordinary forests that we all more readily encounter—younger woods in settled areas, regrown logged areas, and even city trees and parks. Most people can get to parks or semi-wild lands near cities much more easily than to the more dramatic, typically more remote examples. The nearby ones offer enough to be rewarding, and even for those who know wilder woods, the nearby ones can be enjoyable reminders. An old, lightly managed second growth forest offers enough pleasures that it’s important to keep in mind what’s missing—the trunks eight or ten feet thick, and perhaps the old, decaying nurse logs. The most poignant reminders are the huge old stumps still showing the notches which held the springboards loggers stood on with their axes and saws.

I wonder if old forests will last? Humankind encroaches on them, harvests them, introduces unfamiliar competitors, and appears to be changing the climatic conditions of their very existence. It doesn’t look good. Many species diminish and even disappear as the conditions for their lives vanish. Then the biological communities of which they are a part begin to weaken. If climate zones move north, can plants and animals follow along? Sometimes, but when the change is too fast, too far, they simply can’t keep up—how quickly can trees and mushrooms cover new ground? Mountains, lowlands, rainforests, and deserts are each hospitable to certain life while blocking many migrants which can’t live there. No, it doesn’t look good.

Do I want to resist these changes, to help reduce the losses? Of course: my empathy for the lives in the forests and in all of Nature impels me to. And even more, my love for the best possibilities in human awareness calls me to preserve the opportunity for people to engage a fascinating Nature.

Even if we, collectively, grievously wound Nature, in the long run Nature would nevertheless be fine. A few tens of millions of years and the complexities and subtleties would be restored. Nature has enough time. People don’t. Our lives are now, and maybe in the next few thousand years, and whether or not those future lives are lived immersed in a soul-nurturing Nature, a Nature bigger than we are which thus keeps pulling on us and expanding us, that is a choice which we make with our conduct today.

Yes, conserving wildness does temporarily help Nature, yet because of the sufficiency of Nature’s healing time contrasted with the immediacy of our human experience, what is ultimately at stake is our human desire for lives as deep and rich as possible.

Have we finished with Nature? Are we through being fascinated, being challenged, and discovering? Are we through being swept away in awe, being comforted, and responding with art? I hope not. What’s special about engaging wildness? It’s greater than our knowledge. Wildness is grander and stranger than even our imaginations.

Forests give me an experience of beauty and fascination, and I give to the forest my gratitude and thus my caring. When I am able to expand my consciousness sufficiently, my separation from the forest, from Nature, dissolves: instead of me perceiving it, it becomes my way of perceiving. And instead of being its observer, I become its consciousness, its awareness of itself. Now I am at home, in my ancestral way, my home of enchantment. Nature and I are within each other.

I feel gratitude to the sun and earth, the weather, and the trees with their companion plants and animals for becoming these magnificent forest communities. I feel gratitude to the people who have preserved old groves in a society so oriented toward finding money wherever possible. The communities of enthusiastic citizens, government officials, and businesses which came together to keep these groves standing are just as complex as the forests themselves, and just as wonderful. Their efforts come to fruition whenever we walk in the woods, and whenever we, today, choose a similar gift to the future.

© 2005 David Lee Myers

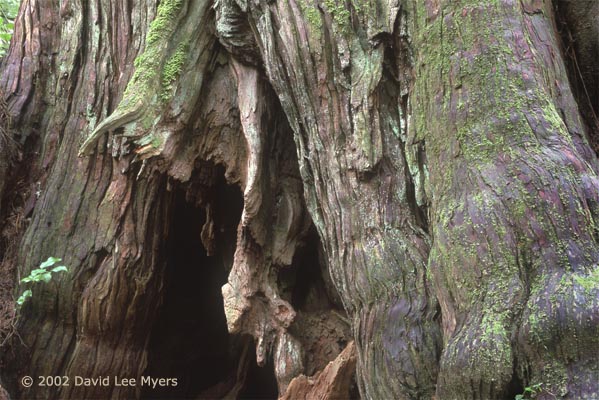

Enduring Trunk. Long Island Cedars, Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, Washington. In this climax forest, all stages of the forest life cycle can be seen. 2002.

Renewal. Long Island Cedars, Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, Washington. In this climax forest, all stages of the forest life cycle can be seen. 2002.

Marbled Murrelet Egshell. The shell likely came from a nest in the large Douglas-fir towering overhead—it’s just the right place for the rare and protected Marbled Murrelet to nest. Fox Creek, Saddle Mountain State Park, Oregon. Camerawork 2002, composite 2006.

Klootchy Creek Giant. The Klootchy Creek Giant stood 216 feet tall, with a 56 foot circumference and a 93 foot crown spread. It tied with a Quinault tree as the country’s largest. In a December 2006 windstorm, a rotted upper portion fell, and in the Great Coastal Gale of December 2007, the whole top fell. Klootchy Creek County Park, Clatsop County, Oregon. Camerawork 2001, composite 2007.

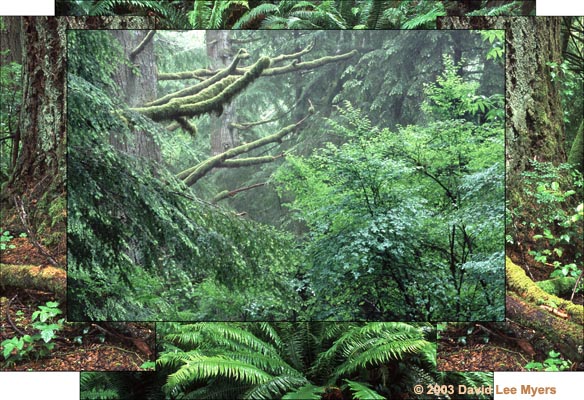

Shively Park Rain. As a photographer I was drawn into the northwest woods by my love of light as it illumined the life of forests. Years later the realization that our Northwest coastal forests are made as much by rain as by light gave me new kinds of pictures to make. In Astoria we may go for a rainy walk in the woods, such as this one in Shively Park. Oregon, 2003.

Trunk with Burls. The burls on this grand old trunk are reservoirs of dormant buds. Such buds can keep the tree alive after higher portions of the trunk die. Long Island Cedars, Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, Washington. 2002.

.jpg?crc=282433889)

Looking up to Maples. Queets River Valley, Olympic National Park, Washington. I saw these two views while lying on the ground and looking up through swordferns and salmonberries growing at the trees’ bases. Spring 2003.